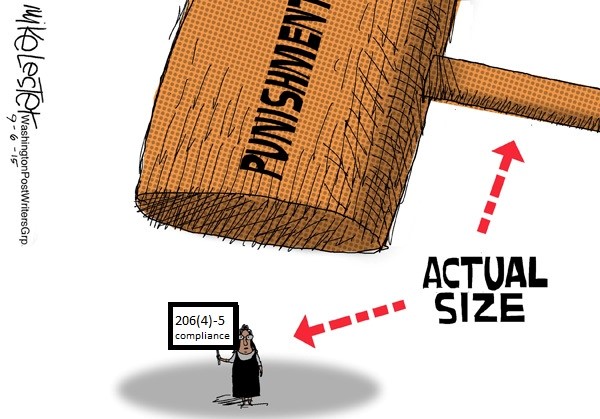

Pershing Square Capital Management has found itself in the unenviable position of having to seek absolution from the Securities and Exchange Commission for the consequences of an unintended $500 pay-to-play error by one of its former analysts, which may result in the hedge fund being forced to return millions of dollars in fees. It has not gone unnoticed by this blog and others that the SEC has made clear it intends for the regulated community to be very, very aware of the restrictions imposed by Advisers Act Rule 206(4)-5 and has little sympathy for the potentially draconian consequences the rule can impose. It has also not gone unnoticed by the regulated community that the penalties for failure to comply with the law can be severe – violators are debarred from receiving payment of fees (to be distinguished from being forbidden to do the work) for a period of two years from the date of the violation.

According to Pershing Square’s application for exemption from 206(4)-5’s penalty provisions, which was filed with the SEC in September but only made public this week, a single Pershing Square analyst made a single $500 contribution to a Massachusetts candidate for governor in excess of the $150 limit proscribed by 206(4)-5. As the law makes clear, it did not matter that Pershing Square employs a robust compliance program and that the analyst’s contribution was made in violation of firm policy and apparently without the knowledge of Pershing Square’s Chief Compliance Officer. It did not matter that the analyst never spoke with the state fund or its representatives. It did not matter that the analyst was arguably not sufficiently senior to fit the definition of a “covered associate”. It did not matter that the recipient of the funds was the sister of family friend who the donor never spoke with. It did not matter that the candidate did not even receive sufficient votes to get on the ballot and it did not matter that the contribution was returned. All that matters under the regulation is that Pershing Square is one of many funds managing the Massachusetts Pension Reserves Investment Fund and that one of its lower-level investment analysts donated to a candidate seeking election to an office (governor) that has the power to appoint members of the state pension fund who, in turn, would have the power to select those firms hired to manage the fund’s money.

From the somewhat-biased perspective of an adviser to those seeking to comply with the myriad of pay-to-play rules at the federal, state and local levels, Pershing’s application for an exemption would appear well-founded and the relief sought appropriate. Past experience, however, has made clear that the Commission has historically viewed the virtues of its enforcement mission as superior to the unintended consequences borne by those who, quite frankly, appear to have done as much as a large operation could possibly do to enforce internal compliance with pay-to-play requirements. One needs look no further than the SEC’s response to another unfortunate Massachusetts political contribution by a former Goldman Sachs investment banker to discern where the Commission’s sympathies are likely to lie.

As stated by Pershing Square in its application for exemption from 206(4)-5’s penalty provisions, the rule “can be violated as a result of circumstances wholly unrelated to the harm the Rule was designed to prevent. . . . Despite the best efforts of an adviser, an employee’s unintentional violation of the adviser’s internal policies could cause the adviser to suffer a financial loss many thousands of times greater than the value of a contribution that the adviser would have never approved in the first place.”

As of yet, the SEC has declined to comment. Gulp.